What Happened to My Station?

Steve Callahan for Radio-Guide Magazine

It’s been good season for tropospheric ducting along the New England shore. You might not be familiar with the term “tropospheric ducting,” but you just might have experienced it and not known why.

We’re all familiar with the way that AM signals bounce at night and come down far from their point of origin. Anyone who has listened to the big 50,000 Watt clear channel AMs knows the thrill of hearing a distant AM on a regular radio. I was once surprised to hear WBZ from Boston while in a traffic jam one night in Atlanta, Georgia. An AM station’s “skywave” component reflects off the ionosphere as it cools down at night and the usually transparent-to-AM layer turns reflective and the AM signal comes back to earth far from it’s transmitter. Frequency and tower height influence the degree of skywave along with seasonal differences and weather conditions.

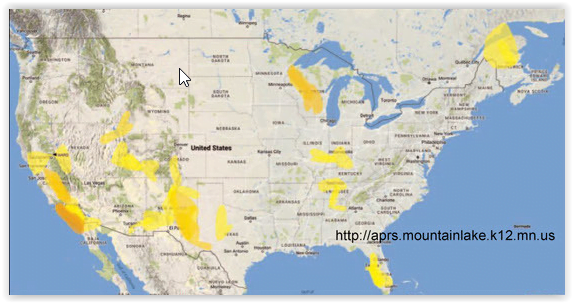

FM also is also subject to a temporary weather condition that can and does send an FM signal far from home. Tropospheric Ducting is a condition when a layer of air is sandwiched between two layers of air that are at a different temperature than the center of the sandwich. The FM signal gets into the center of the sandwich and is “ducted” or channeled long distances from its usual service area.

Tropospheric ducting is very temporary, only an hour or two at a time, and can be somewhat expected during the right weather conditions. My experience is that it is more common along the shoreline.

I was once at small FM station on Cape Cod repairing a transmitter and the work took longer than I had expected. It was after dark by the time I turned the transmitter back on, checked the meter readings, buttoned up the transmitter building and headed home. I had the newly repaired station on my car radio and just a few miles down the road, the programming of the station suddenly changed. I was now hearing a New Hampshire station on the same frequency! I thought, “Drat! – that repair didn’t last long. So I did a quick U-turn and headed back to the transmitter as fast as I could. As I threw open the transmitter building’s door, I saw that all of the transmitter readings were normal and just as I had left them. As I tried to drive home the second time here was no sign of the New Hampshire station and I was left scratching my head.

Years later I was working at a high powered FM station on a mountain top in Maine. I had spent most of the day working on the site and I was quite pleased that my efforts resulted in a successful conclusion. I got in my car, drove down the mountain and headed home. I was listening to the station in my car and about 45 minutes from the transmitter site the programming suddenly changed. Now I was listening to a Cape Cod FM station which I knew was almost three hours away! I remembered back to my first experience on Cape Cod and as I drove south, the Maine station’s signal came back and all sounded as it should.

I was Director of Engineering for a small FM station in Rhode Island when I got a call that some of our loyal listeners along the southern shore were asking why we had suddenly changed our format to country. I quickly spun the dial of my car radio to our frequency and, yes indeed, there was full-stereo, bootscootin, country music coming out of my speakers. When the song ended, there was a commercial spot for a car dealer in Ocala, Florida. Tropospheric ducting strikes again! Within an hour, the Florida FM signal faded away and our local signal returned. During my tenure in Rhode Island it was not unusual to have a couple of tropospheric ducting episodes a summer. Usually a co-channel FM signal from the top of the Empire State Building in New York City was the ducted-in culprit and it left as quickly as it arrived. My clue in Rhode Island was if there was heavy sea fog in the early morning along the southern coast, conditions were right for some tropospheric ducting that day.

Just last month, another Rhode Island FM station called me to ask if there was a reason why their signal just got noisy and their listeners were complaining. You guessed it – there was heavy sea fog that morning and another co-channel FM station was being ducted into Rhode Island. In less than an hour, the fog lifted and their signal returned to normal.

Shortly after that, an old friend of mine called and asked if there was any reason why a Rhode Island station’s air signal would be coming out of his station’s off-air studio speakers in Portland, Maine that morning. I told him that it was most likely some co-channel tropospheric ducting along the Maine coast or the Rhode Island coast and it would go away in an hour so. My friend was greatly relieved and said he would pass the information along to his anxious station manager.

My experience is that tropospheric ducting affects cochannel stations, which are stations on the same frequency, and the signal that is negatively affected could be the offending signal another day. There is a website (www.dxinfocenter.com/tropo.eur.html) that tries to predict when weather conditions are right for tropospheric ducting. The condition will dissipate as soon as the weather changes. My advice is, if this happens to your station, first, try to calm down your general manager, explain to any of your listeners who call in that it is an occasional, natural occurrence which will go away soon. Then you can sit back, relax, and revel in what the mixing of weather, temperature and frequency modulation can do.

Steve Callahan, CBRE, AMD, is the owner of WVBF, Middleboro, Mass. Email at: wvbf1530@yahoo.com